The Bike Rack’s a Worm

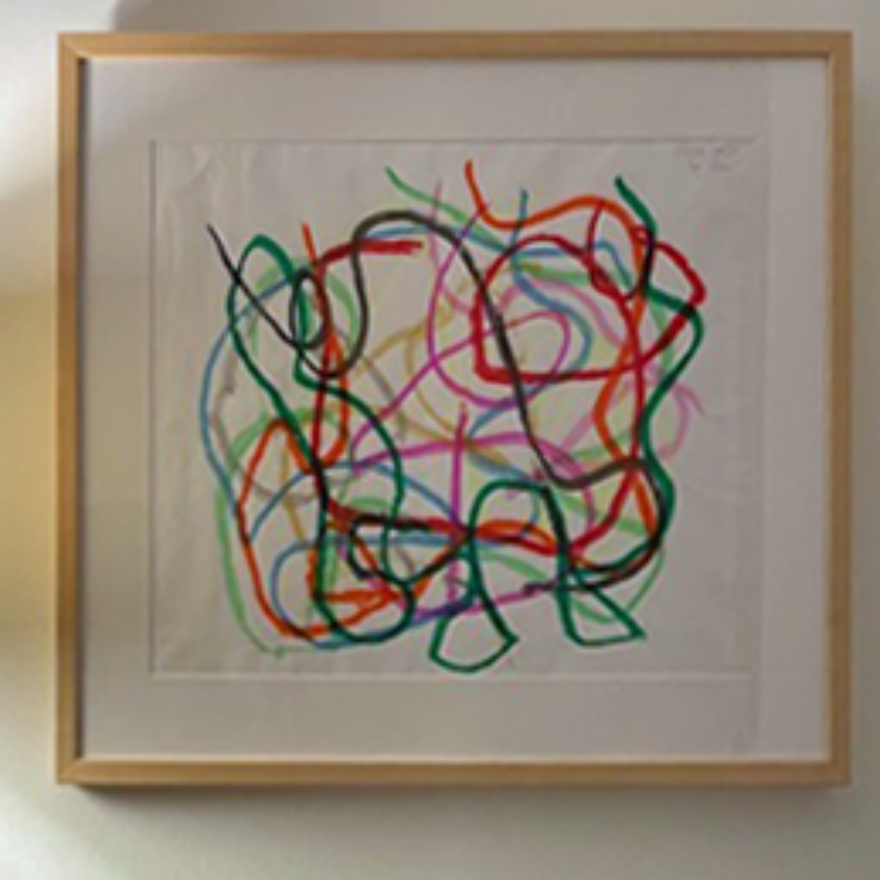

More than a year into the pandemic, I finally created a proper remote work nook. I put a lamp next to my table, a desk organizer on the radiator, and–most important for our Zoom world–a picture on the wall behind me. It’s called “Color Maze.” It’s a series of bright, watercolor curved lines that weave in and out of one another, and the artist is my 4.5-year-old son, Evan. I had it framed. And when I placed it on the hook, the area felt complete.

As we start to emerge from pandemic parenting, like so many parents there are so many ways that I feel depleted. One reason, especially in those first few months of lockdown, was that I was even more anxious than usual about how to fill my children’s time and keep them happy. But as the months went by, in part out of necessity, I started doing less work to shape their play. I spent more time watching them and less time organizing them, and in the process, their play began to shape my work. My son’s creativity became a source of inspiration–and now a literal backdrop–for my own.

I’m a content strategist at G&A, which means I help to uncover a project’s big idea and its stories, and collaborate with a team of designers to bring them to life. Creating our best work requires courage and vulnerability. It requires an openness and lack of inhibition that, I discovered, my son has in spades.

Evan sees endless possibilities. When he looks at an object, he doesn’t filter it through its intended function but instead imagines all that it resembles or could become. He’s a master at what we adults call “divergent thinking,” coming up with as many possible ideas about something in a short amount of time. To him, the bike rack outside Marymount Manhattan college looks like a worm and a partially eaten piece of toast becomes a whale. The possibilities for toilet paper and paper towel rolls are of course infinite–including binoculars for a bear hunt or the base of a lamp if you just hang a plastic cup on one.

Evan’s imagination so inspired me that I started hosting creative exercises during weekly meetings to encourage my colleagues’ quick, unrestrained thinking. After watching Evan wrap a strainer from an empty feta cheese container around his foot, I put a photograph of it up on screen and asked colleagues what it could be, generating responses that included: monkey hat, bug zapper, and ancient form of GPS.

For Evan, the journey is the destination. Not only is he not worried about where he’s going, but his joy is also in getting lost. On a bicycle ride, he will unexpectedly stop to pull a berry from a tree, follow a bunny, or speed ahead to find out the breed of a neighbor’s dog. As we walked to school, he stopped to look at the Spanish words printed on the side of a breakfast cart, stepped only on the white lines of the crosswalk to avoid the “lava,” and stopped to print letters in the snow with his feet. I often eye my phone, nervous about the time. But I also realize that during these detours he’s exploring nature, learning a new language, and noticing patterns.

And I’ve tried to follow his model in my work. On a new project, I found myself understanding its goals, but lost, at first, in how to reach them. Channeling Evan, I decided to focus less on the endpoint and instead, just get started. My colleagues and I went down some unknown and unexpected paths to explore new ideas and ways of expressing them. And in the process, we built team trust, grew our skills, and also happened to reach our goal.

If Evan’s unencumbered by goals, he’s also blissfully unhindered by the need to be perfect. I watch with awe as he dives right into putting something together, just as quickly takes it apart and then puts it together again. If I hesitate to disassemble the words I’ve formed in Bananagrams so I can create combinations with more of my letters, he breaks apart a pattern puzzle without hesitation as many times as he needs to until he’s able to assemble them so they fit. Where I see risk, he sees discovery.

But I’ve been changing. At G&A, we embrace the process of building something rapidly to test it so that we know what works, what doesn’t, and how we need to rebuild it. In the last year, we’ve been creating prototypes earlier and earlier in our design process, and the result is that we’ve actually lessened our risk rather than increase it. We figure out quickly what pieces don’t fit or need to go somewhere else and then work to put them back together into something that not only we find engaging and beautiful but that we know, through our user testing, museum visitors will too.

For Evan, there’s no dream too big. When we go to the MET, he loves tossing pennies into the fountain in the American Wing, and I love asking him what he’s wishing for. Recently he said: “I wish everything in the Museum would turn real” and “I wish the roof would burst open.” And while reading a book before bedtime, he said: “I wish I were in the book, and you’d read me up.” He’s not even five, but he’s imagining experiences that design studios like us are creating now: immersive rooms where you feel as though you’ve stepped into a painting, portraits, and historic photographs that come to life through artificial intelligence.

What inspires me most of all is that my son moves through the world with the confidence to express himself freely. The other morning, Evan and his two-year-old sister, Leah, were sitting on a step stool in the kitchen drinking smoothies, and Evan said, seemingly out of nowhere: “It feels good to be ourselves.” And I see that this sense of self is what gives him the freedom to imagine, to wander, to dream. At work, we’ve been actively cultivating an environment where everyone feels heard and encouraged to share their ideas. It’s a goal in and of itself; it’s also essential to creating our best work.

Thankfully, it looks like the pandemic part of pandemic parenting will be over soon. And hopefully, our patterns of work, school, and childcare will start returning to normal come fall. I also hope–even as Evan and I spend fewer hours in the same space–that in the time we do have together, I keep observing and learning from him. To remind me, I’ll keep that painting behind my desk.